Issues with human error are common across the web. For example, Microsoft conducted research in 2011 and found that users made spelling mistakes in 10-20% of searches. However, the effects of an unforgiving site are felt more keenly by those with cognitive impairments. This is an issue for users who have language-based disabilities, but it also has a huge impact on those with memory impairments like dementia.

To combat this, you need your site to be as error tolerant as possible, and a large portion of these pain points are revealed when content is inputted. I often find myself typing too quickly and placing letters in the wrong order, so if a site can compensate for these small, and very human, errors it will prevent unnecessary frustrations.

Features such as autocorrect (automatically correcting common spelling errors) come as standard in a lot of devices and operating systems and can be very useful, but another great innovation that you can add yourself is autocomplete.

What is autocomplete?

Autocomplete is a feature that attempts to ‘guess’ what a user has started to type, and is often seen on form inputs. It provides options that they can select from, based on the information the user has already provided (usually after a few characters have been entered), and offers to complete the entry for them. It can help users find results more quickly, especially if they have trouble remembering what they are looking for, or how to spell it. This can also help people with ADHD or autism, who can often become overwhelmed by too many options.

This can be caused by form elements that contain long dropdowns, for example selecting a country from a list of every country on Earth. Examples like this are a perfect candidate for autocomplete, as this features search against a large list of options, but filters those options the moment a user starts interacting based on the content they’ve entered.

This approach is actually one of the new success criteria that the Cognitive and Learning Disabilities Accessibility Task Force (COGA) added into the recent WCAG 2.1 update (the latest guidelines for how your site should be accessible). It’s called “Identify Input Purpose” and refers to this ability to programmatically determine the purpose of an input field in order to make collecting data from a user easier. Here, they explain how autocomplete can also help users with dyslexia and dyscalculia:

Problem:

My address is so complicated. There’s lots of numbers and long words. It’s hard to type it all without making mistakes.

Works well:

I love websites that can automatically fill it all in for me. Then I don’t have to work so hard to get the numbers and spelling right.

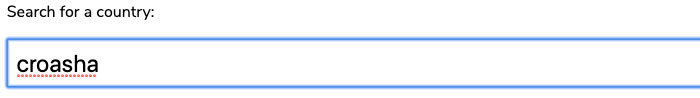

This can be a powerful feature, but there is a catch - autocomplete often still requires a degree of precision to use. This is because, by default, many of the libraries used to add this aren’t great at accommodating for human errors. As a result the usefulness of the feature is dependant on the way a user searches, and errors inputting content can actually offset the time saved by implementing autocomplete, as a user would need to delete the incorrectly entered content before re-typing it in order to find the correct option. This is what I call “strict search” and, when implemented in this fashion, can make the process longer than inputting content regularly.

“Strict” search

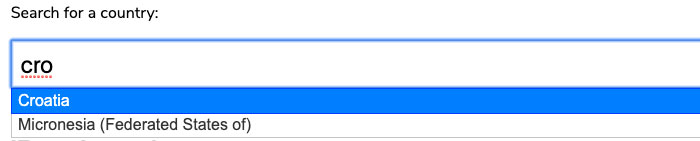

A good example of this is the most used autocomplete library on the web - jQueryUI Autocomplete (which is part of jQuery’s larger UI library). This is easy to implement, but as we mentioned earlier, this form of autocomplete suffers from the issue of only returning results that are spelt correctly, as opposed to returning results that are close to an intended answer. If we were hypothetically trying to search for the country ‘Croatia’ from a list of every country, using this library, here are the search examples that would return it as an option:

- Cro (options appear after typing 3 letters, and these letters are in the correct order)

- Croatia (the country name itself, spelt correctly)

It does what it should, but it’s not lenient to human error:

“Fuzzy” search

You’ve probably seen autocomplete on sites like Google and Amazon, and you’ve probably also seen they’re good at ‘guessing’ what you’re searching for. This is known as “fuzzy” searching.

Fuzzy searching can search for results in a list like the example above, but also in a far more lenient way, without relying on an exact match with what has been inputted. It includes misspelt words, the correct letters but in the wrong order, or alternative spellings of a word (i.e. something that ‘sounds’ phonetically like the word).

Not only that, but fuzzy searching can take in associated or related information for each search result, rather than just the word itself. For example if a user is searching for a book, they may want to search by author, or ISBN number - not just by title. This is all common user behaviour when searching for anything, and allowing it on your site makes your user experience more accessible.

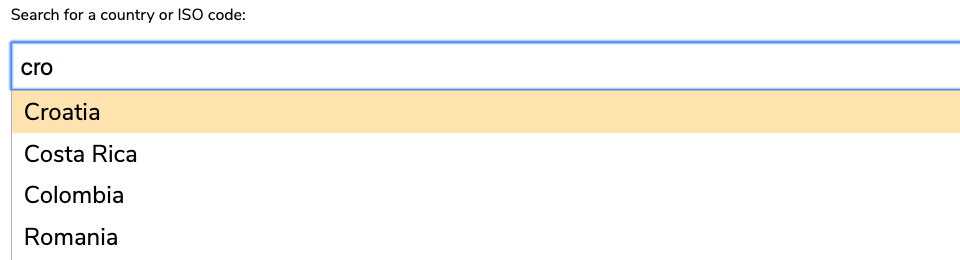

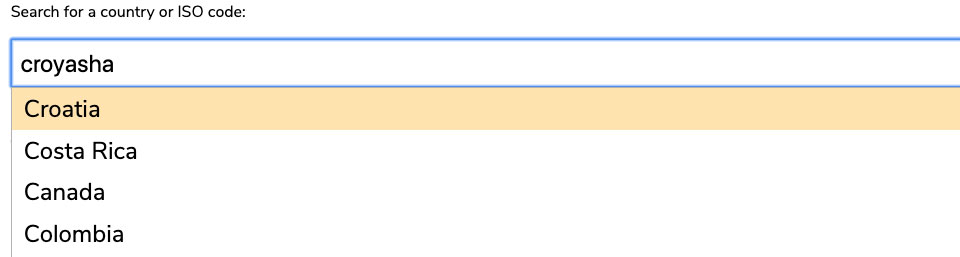

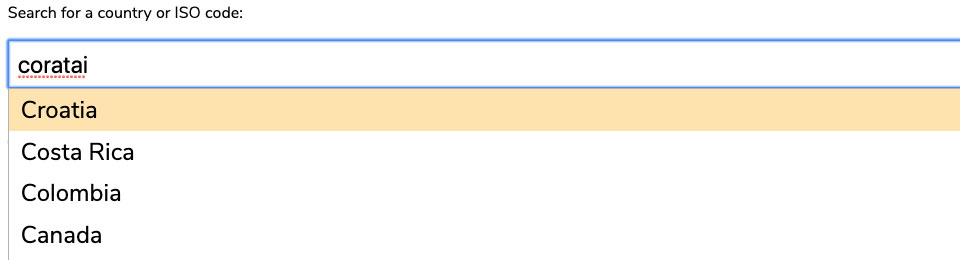

Below is an autocomplete for the same list of countries as above, but with a couple of differences - it allows for fuzzy searching, and can interpret additional information to help the user find the result they may be looking for. In this case, it allows users to search by ISO country code as well as the country itself. Here are just a few examples of text that a user could enter into the form field to return Croatia as the top result:

- Cro (options appear after typing 3 letters, and these letters are in the correct order)

- Croatia (the country name itself, spelt correctly)

- Croasha (mis-spelling of the ‘tia’ at the end)

- Coratai (All of the letters in ‘Croatia’, but in a completely wrong order)

- Roatia (missing the first letter, likely from a quick typing error)

- HN (the ISO country code)

- Crosha (A misspelling)

- Crowaysha (Written as the word sounds)

- Croaysha (Same as above)

And many more I likely haven’t thought of…

Types of “fuzzy” searching

I didn’t create the logic for “fuzzy” searching, I’m merely showing how implementing better searching methods can benefit a wide array of users. I will, however, provide examples of them in this chapter’s practical example, so that you can easily recreate the behaviour and implement it into your own sites. There are two main approaches I have found relating to fuzzy searching.

Jaro–Winkler distance algorithm

This algorithm measures how many characters there are in common between the text that the user has entered and a list of possible autocomplete options. This combats human error resulting from text being entered in the wrong order, but also takes into account the idea of a user incorrectly spelling a word through sounding it out but getting a fair amount of the letters correct. For example, Croatia is pronounced ‘cro-ay-sha’ which, despite being the incorrect spelling, has 5 of the 7 letters in common with the correct spelling.

Practical example

Here’s one I made earlier for you to check out!

learna11y.com/examples/6-cognitive-impairments/

The approach used in the images above match the functionality of the example I’ve created, using a library called Missplete. The code was created by a developer called Xavi Caballé. In the practical example you’ll find links to all of his work.

Levenshtein distance - Fuse

The Levenshtein distance (also known as edit distance), is the minimum number of single-character edits (insertions, deletions or substitutions) required to change one word into another. In this case, it compares what the user has entered against the list of possible options, and determines how it could get to a result with the fewest edits. The most used version of this with autocomplete was created by Kiro Risk, a Software Engineer at LinkedIn, who created Fuse JS. Although I didn’t implement this in the practical example, you’ll find links to his work there if you’re interested.

Which should I use?

Both provide a significant improvement on standard “strict” searching by allowing for human error, and by allowing the search to associate multiple pieces of information with each result. In research conducted on both, Jaro-Winkler was considered the faster of the two approaches, but the Fuse library is more heavily supported as a project. In my opinion there is little difference between the two, so you can simply choose which library fits most neatly with your needs.

Whichever you choose, it’s clear to see that fuzzy searching holds the potential to help more users.

This component is one of many that you often see on the web that could be more accessible. There’s a host more like it in my book, which you can check out if you’re interesting in learning more about accessibility (even if you’re not a developer!).